Why Inclusive Language Is Still Important

an article first published in Christian Feminism Today

an article first published in Christian Feminism Today

“We don’t need to do inclusive language any more,” some of the young women tell my professor friend in her intern classes at a theological seminary. “That was important when you were going through seminary because there were all men. Inclusive language isn’t important anymore because now women can be leaders in church and are in the workplace big time.” My friend says that when they go out into churches, these students discover that gender discrimination, although often more subtle now than in the past, is still all too prevalent.

For ministers and laypeople of all genders, inclusive language is still vital to social justice and equality. In 1974, in All We’re Meant to Be, and more emphatically in the 1986 and 1992 editions of this book, Letha Dawson Scanzoni and Nancy A. Hardesty advocate for inclusive language and give biblical support for their belief that “women have just as much right as men to think of themselves in God’s image.”[i] In 1983, Virginia Ramey Mollenkott writes: “It seems natural to assume that Christian people, eager to transmit the Good News that the Creator loves each human being equally and unconditionally, would be right in the vanguard of those who utilize inclusive language. Yet a visit to almost any church on Sunday morning indicates that alas, it is not happening that way.”[ii] In 1988, Nancy Hardesty also makes a persuasive case for inclusive language as central to the gospel,[iii] and in 2010 she reinforces use of female and male images of the Divine to affirm the biblical declaration that all are made in the Divine image.[iv]

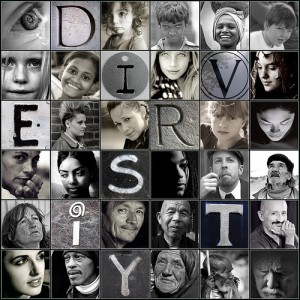

So why is there still so much resistance to inclusive language? It doesn’t seem to matter that Genesis 1:27 clearly reveals female and male in the Divine image. The language of litanies and hymns and visual images in most churches, synagogues, and temples reveal worship of a white male God. Many still use exclusively masculine language for humanity as well as for divinity. I’ve even heard the argument that changing “man” to “mankind” makes the term inclusive. Although inclusive language for people made the grammar books in the 1980s, “man,” “mankind,” and other exclusive words persist in many churches and in the media. As Hardesty declares, there is “no excuse to exclude half the human race when speaking or writing.”[v] From these patriarchal practices follow patterns of dominance and subordination, resulting in the interlocking oppressions of sexism, racism, heterosexism, classicism, ableism, rape of the earth.

Some people argue that inclusive language is a “trivial” issue and that those who advocate for it are just too “sensitive.” But if language is unimportant, why do they react with such anger, as though we have brought pornography into worship, when we refer to God as “Mother” or “She”? No better proof could be found for the bias against the feminine and the need to overcome it by calling God “She.”

Marg Herder, Director of Public Information for Evangelical & Ecumenical Women’s Caucus, attributes this bias to the fact that “language was created by patriarchy.” She writes: “Think it doesn’t matter that God is referred to almost exclusively as ‘He’? Sure, you’re enlightened enough to think of God as a force, or a presence, or as Spirit. But when you need a pronoun, what pronoun do you reach for? It matters. It is huge. Try calling God by female pronouns in almost any Christian church sometime. See how that goes over. Try referring to God as ‘She’ in your own speech. Feel kinda like you are breaking a rule, being bad?”[vi]

Womanist theologian Monica A. Coleman believes that it’s important to use female language for Deity because of the prevalence of patriarchy. “And the fact that people rail so much against female language for God shows how important it is. It’s just amazing to me how much people are attached to God’s being a man.”[vii]

When she was a student at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary working on an inclusive language worship resource for use in chapel, Rebecca Kiser also discovered how resistant people are to changing exclusively male language for Deity. “Inclusive language about people was a given by that time, but inclusive language about God was the cutting edge. At one point I got into a really big discussion with a systematic theology professor about language for God. We were trying to say ‘Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer,’ and he just went ballistic. He got really red-faced and said that if you weren’t baptized in the name of the ‘Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,’ those exact words, it was not a Christian baptism and didn’t count. Some people were really invested in the maleness of the language. Words have power.”[viii]

In advocating for inclusive worship language, Judith Liro, an Episcopal priest, uses this metaphor: “Several factories are built on a river, and they pollute the water of a village downstream. A hospital is built to treat the illnesses that result, but there is still a need to track down the source of the pollution, to stop the pollution, and to clean up the water itself. Many organizations including the Church do the important work of the hospital. Yet I have also come to realize that the Church is one of the factories that contribute to the problem. Our liturgical language with its current, heavily masculine content supports a patriarchal hierarchical ordering. Most are simply unaware of the power of language. The status quo that includes the exploitation of the earth, poverty, racism, sexism, heterosexism, militarism. . . is held in place by a deep symbolic imbalance, and we are unwitting participants in it.”[ix]

The prevalent worship of an exclusively male Supreme Being is the strongest support imaginable for the dominance of men. Some advocate using only female divine references for the next 2000 years to rebaptize our imaginations that have been so fully immersed in masculine divine images. Although worship services with only feminine language will help raise awareness, I advocate gender-balanced language to support equal partnership.

The only way to begin in some faith communities is with non-gender divine language; however, I believe that to be truly inclusive we need to move toward language that Rebecca L. Kiser, a Presbyterian pastor, calls “gender-full rather than genderless.”[x] Because of centuries of association of “God” with male pronouns and imagery, this word generally evokes male images, so it is not truly gender-neutral. Referring to “God” as “She” brings gender balance.

The Bible provides many female divine names and images. “Wisdom” (Hokmah in Hebrew Scriptures; Sophia, Greek word for “Wisdom,” linked to Christ in Christian Scriptures) stands out in the book of Proverbs (1, 3, 8), in the books of Wisdom and Sirach in the Catholic canon, and in 1 Corinthians 1:18-31. Among other female divine names and images in the Bible are “Mother” (Isaiah 66:13, 42:14, 49:15); “Mother Eagle” (Deuteronomy 32:11-12); Ruah (Hebrew word for “Spirit,” Genesis 1:2); El Shaddai (Hebrew for “The Breasted God,” Genesis 49:25); Shekinah (feminine Hebrew word used in the book of Exodus to denote the dwelling presence and/or the glory of God); “Midwife” (Psalm 22:9-10); “Mistress of Household” (Psalm 123:2); “Mother Hen” (Matthew 23:37); “Baker Woman” (Luke 13:20-21); and “Searching Woman” (Luke 14:8-10).[xi]

Naming the Divine as “Wisdom,” Sophia, Hokmah, “Mother,” Ruah, “Midwife,” “Baker Woman,” “She,” and other biblical female designations gives sacred value to women and girls who for centuries have been excluded, demeaned, discounted, even abused and murdered. Exclusive worship language and images oppress people by devaluing those excluded. This devaluation lays the foundation for worldwide violence against women and girls. In the U.S. alone, every fifteen seconds a woman is battered. One in three women in the world experiences some kind of abuse in her lifetime. Worldwide, an estimated four million women and girls each year are bought and sold into prostitution, slavery, or marriage. Two-thirds of the world’s poor are women. “More girls have been killed in the last fifty years, precisely because they were girls, than people were killed in all the battles of the twentieth century. More girls are killed in this routine ‘gendercide’ in any one decade than people were slaughtered in all the genocides of the twentieth century.”[xii] There are many more alarming statistics on worldwide violence and discrimination against women and girls. Theology and worship that include females names and images can make a powerful contribution to a more just world.

Inclusive language also helps to heal racism and supports the sacred value of people of color by changing the traditional symbolism of dark as evil and white as purity. We can name Deity as “Creative Darkness” from which the universe came (Genesis 1:1-2), and symbolize darkness as a sacred well of richest beauty (Isaiah 45:3). We can celebrate the life-giving darkness of the “Womb” (Psalm 139:13-14) and of the “Earth” (Psalm 139:15-16).

Including multicultural female divine images along with male and other gender images in worship contributes to equality and justice in human relationships and right relationship with the earth, while expanding our experience of divinity. Through this inclusive worship we spread the Good News of liberation and abundant life for all.

Copyright 2013 by Jann Aldredge-Clanton and EEWC-Christian Feminism Today. All rights reserved. Originally published on the Christian Feminism Today website (http://www.eewc.com/inclusive-language-still-importan/). Reposted with permission.

[i] Letha Dawson Scanzoni and Nancy A. Hardesty, All We’re Meant to Be: Biblical Feminism for Today, Third Edition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 18. All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation, First Edition (Waco, TX: Word, 1974). All We’re Meant to Be: Biblical Feminism for Today, Second Edition (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1986).

[ii] Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female (New York: Crossroad, 1983), 1-2.

[iii] Nancy A. Hardesty, Inclusive Language in the Church (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1988).

[iv] Nancy Hardesty, “Why Inclusive Language Is Important,” Christian Feminism Today. Online: http://www.eewc.com/christian-feminism-basics/.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Online: http://www.margherder.com/musicLyricsAName.htm; https://jannaldredgeclanton.com/blog/?p=959

[vii] Jann Aldredge-Clanton, Changing Church: Stories of Liberating Ministers (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2011), 157-158.

[viii]Ibid., 282.

[ix] Ibid., 272-273.

[x] Ibid., 287.

[xi] See Mollenkott, The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Female; and Aldredge-Clanton, In Whose Image? God and Gender (New York: Crossroad, 2001), and In Search of the Christ-Sophia (Austin: Eakin Press, 2004).

[xii] Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide (New York: Knopf, 2009), xvii.

Now let’s talk about hymn texts!