Dr. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott’s Review of Intercultural Ministry: Hope for a Changing World

In the wake of the tragedy in Charlottesville, questions Grace Ji-Sun Kim and I raised in the Introduction to Intercultural Ministry keep coming to me: Will intercultural churches advance racial equality and justice? Will they help eliminate racially motivated hate crimes? In the midst of important conversations on how to dismantle white supremacy and white privilege, I’ve wondered how things would be different if there were more intercultural churches. What if people of color and white people come together in all churches, giving equal power and value to each, centering the voices and experiences of people of color who have been marginalized? What happens when we experience community together?

Although Sunday morning continues to be one of the most segregated times in America, more than fifty years after Martin Luther King’s indictment, there are signs of hope and change. Intercultural Ministry includes chapters by people who are meeting the challenges of building intercultural churches and ministries. They write about practical strategies for building intercultural churches and future possibilities. In our Conclusion we summarize this hopeful challenge: “The future of intercultural ministry lies in our willingness to claim our prophetic calling to make reality the gospel vision of radically inclusive love and justice. Those in the dominant culture find freedom from the chains of power and privilege, and those who are marginalized find freedom from the chains of oppression through the liberating power of the Resurrected One” (p. 205).

Many thanks to Dr. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott for this review of Intercultural Ministry: Hope for a Changing World, originally published in Christian Feminism Today.

Over fifty years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King said that Sunday morning is one of America’s most segregated hours. Partly in response to that assessment, intercultural congregations urge interaction of people across racial, ethnic, and national boundaries. The goal: to value and celebrate each group’s traditions (p. ix); in fact, to build not so much an intercultural ministry as an intercultural community (p. xii).

According to Kim and Aldredge-Clanton, our Christian mandate is to preserve hope in a world full of violence, poverty, predatory lending, and deportation threats, and to be there for the people who are under threat. To accomplish this, the clergy must emerge from the pulpit and into the streets, and members must leave the pews to become reconcilers and healers of relationships. We must create communities that oppose emphasis on differences, instead welcoming the Holy Spirit’s work of radical reconciliation.

To help make all this happen, the editors have brought together fifteen pastors, theologians, teachers, and professors, all of whom share the concept that best describes the book’s purpose. Each was asked to depict the joys and trials of intercultural ministry as “bringing people of various cultures together to engage in learning from one another, giving equal value and power to each culture” (p. x).

In a delightful essay called “Long Thread, Lazy Girl,” Rev. Katie Mulligan describes her eager haste as her mother taught her to make needle-threaded paintings. She was often told to use a shorter thread—to stop trying to cut corners and save time by using longer threads. Because many of us have been given a sense of white entitlement that often extended into ownership of other people, we must now dedicate ourselves to working patiently: “Long thread, lazy girl!” (p. 166)

Leader after leader bears witness to how exhausting this work can become. Reading these witnesses, I felt thankful to have been present in Durham, North Carolina, when composer-musician Carolyn McDade led a women’s a capella workshop with a group of white women from one church and black women from another. Since everyone was female, Christian, and loved Carolyn’s music, what could go wrong? But there were so many differences of expectations and leadership that the weekend was profoundly uncomfortable, especially for the white women, who were getting a crash course in sharing the decisions. When we add race and religious practices to such matters as sexual orientation, gender identity, mental and physical ability, and generational attitudes, we begin to catch a glimpse of the kind of patience a multicultural ministry can call for.

Here are just a few of the remarks that especially struck me from people who have devoted their lives to a multicultural, multiracial, and multigenerational healing ministry. Rev. Peter Ahn, who works with the Metro Community Church in northern Jersey (weekly attendance 65 percent Asian, 15 percent black, 10 percent Hispanic, 10 percent white) emphasizes finding our communality in our weaknesses rather than our strengths. Looking at the moments of brokenness in the Scriptures and in the lives of his congregants, Ahn remarks that “Empowering people to follow Jesus is exponentially more effective than guilt-tripping people” (p. 156). He urges fellow leaders to “tap into their own brokenness and show people how their mourning can be turned into dancing” (p. 160). Sounds right to me.

Bishop Karen Olivetti, who helped develop the Glide Memorial Church (the 11,000-member spiritual center in San Francisco) insists that in the body of Christ, where dividing lines fall way as we all become one body, “the particularities of our differences” do not “fade away.” “In fact, 1 Corinthians 12 details the important role that diversity plays in providing wholeness. Differences are required if the body is to thrive” (p. 148). Thus the leaders must constantly be asking, “Whose voices are still silenced? Whose lives are kept in the shadows of the margins . . . sex workers, staff, addicts, donors, congregants, the housed . . . the homeless?” (pp. 142–43).

Clergy or laity, Christian or otherwise, all of us carry a vital responsibility of providing hope for our rapidly changing world. Intercultural Ministry will help every reader discern diversities that had previously seemed invisible. And it will provide incentive and techniques to transcend those challenges. What a brave undertaking!

Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, review of Intercultural Ministry: Hope for a Changing World, originally published in Christian Feminism Today. Reposted with permission.

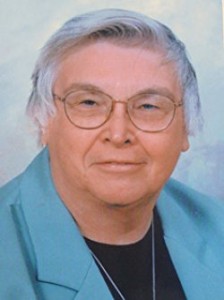

Dr. Virginia Ramey Mollenkott is the author or coauthor of 13 books, including The Divine Feminine: The Biblical Imagery of God as Feminine and Is the Homosexual My Neighbor? a Positive Christian Response (coauthored with Letha Dawson Scanzoni). She is a winner of the Lambda Literary Award (in 2002) and has published numerous essays on literary topics in various scholarly journals. In 1975, she spoke at the first national gathering of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus in Washington, D.C., and delivered plenary speeches at almost every gathering of the organization over the next 40 years. She has lectured widely on lesbian, gay, and bisexual rights and has also been active in the transgender cause. Mollenkott is married to Judith Suzannah Tilton and has one son and three granddaughters. She earned her B.A. from Bob Jones University, her M.A. from Temple University, and her Ph.D. from New York University. She received a Lifetime Achievement award from SAGE, Senior Action in a Gay Environment, a direct-service and advocacy group for seniors in New York City in 1999. At age 85, Virginia Ramey Mollenkott continues to use her doctorate in English to share insights with folks who visit the EEWC and Mollenkott websites, and with elderly people in the Cedar Creek educational programs. She has recently taught an Elderhostel course on the poems of the Rev. Dr. John Donne, and is now preparing a Fall course on John Milton’s Paradise Lost. She deeply regrets that her severe arthritis forbids her presence at recent and wonderful street protests.